University of Georgia Athletics

Past & Present: Carter, Stinson Have Shared Experience

February 18, 2021 | Baseball, General, The Frierson Files

By John Frierson

Staff Writer

Where Steve Carter has been, Josh Stinson would like to go: the big leagues. Where Stinson is now, as an African American on the Georgia baseball team, Carter was more than 30 years ago.

Recently, Carter and Stinson participated in a Zoom meeting, sharing their stories and experiences in baseball, as Bulldogs, and beyond. Stinson, 20, is in his second season with the Bulldogs, still technically a freshman since last season was cut short by the pandemic. Carter, 56, lives in the Washington, D.C., area and is the Deputy Director for Facility Operations for The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, Parks and Recreation.

In 1986, Carter became the first African American scholarship baseball player at Georgia. He was a pioneer and didn't know it, only learning that he was the first earlier this month.

"When I first stepped foot in Athens, it was beautiful, it was a great campus, a great baseball environment, and the first day of practice it did not matter to me that all of my teammates did not look like me," he said. "What mattered to me is we all had the common bond to be better baseball players and better representatives of the community."

Stinson is an outfielder from Lawrenceville, Ga., and playing baseball for Georgia is "like a dream come true," he said.

"Just always seeing Georgia on TV, always hearing about Georgia and how good of a school it is, and having the opportunity to come here, it's just something that I feel like I'm supposed to be here and I'm just thankful that I am here," he said. "It's been a really good transition from high school to here. Everybody's been so accepting and just ready to work and help me out, help me fulfill my potential and become the best baseball player, student and person that I can be."

Growing up "a country boy" in Charlottesville, Va., Carter played multiple sports and saw more diversity in football and basketball than he did baseball, which he said "probably had three or four African American players" on his high school team. Stinson, who attended Grayson High School, a sports powerhouse in the state, had a similar experience in his years playing football and baseball.

"Baseball's not as diverse but it's still pretty open," Stinson said. "Even though there weren't as many African Americans or Black people on my teams, they never really looked at me as any different. They were always pretty open to me, they wanted to be friends with me, like they were my teammates before color even mattered."

Georgia's baseball team had two African American players on the roster last season and there are five in 2021 as the 12th-ranked Bulldogs open their season this weekend with a four-game series against Evansville at Foley Field.

The Bulldogs don't have that "many people that look like me," Stinson said, "but they were still open to taking me in and they still got to know me. I feel like they respect me as a person, so all is good."

During his two seasons with the Bulldogs, in 1986 and '87, after starting college at Hagerstown (Md.) Community College, Carter led the team in at-bats each year. In 1986, he led Georgia in hits (73), runs scored (65) and stolen bases (10). As a senior in 1987, Carter was an All-SEC outfielder on the Bulldogs' first team to make it to the College World Series. In seven postseason games that season, Carter hit .345 and drove in nine runs.

Carter was one of six Bulldogs selected in the 1987 MLB Draft, picked in the 17th round by the Pirates. Back in high school near Charlottesville, Va., Carter's coach was a scout for the Pirates, so it was a relationship many years in the making.

Playing for the Pirates' Triple-A club in Buffalo in 1989, the team was on the road in Nashville, Tenn., when Carter got "the call of a lifetime." Andy Van Slyke, one of the Pirates' star outfielders, was injured and Carter was being called up to the big leagues. He made his Major League debut that night, against the Montreal Expos.

Before leaving Nashville to join the Pirates, he had to call his mom who had raised four boys by herself.

"I said, 'Mom, I'm going to the big leagues.' And then you just heard silence from both us," he said. "We were weeping and crying, and she said, 'What does this mean?' I said, 'Mom, it means I fulfilled a dream.' From a snotty-nosed, buck-toothed, nappy-head boy that had holes in his shoes and people used to laugh at, we were going to the big leagues."

As Carter told the story, it was impossible not to get goosebumps.

"Just knowing that all your hard work paid off, that's got to be a moment like no other, a moment you're going to remember for the rest of your life," Stinson told him. "I just hope that one day I can feel that moment or experience that moment in some way, and to just know that everything I did was worth it."

In more than eight years as a professional baseball player, Carter played in 14 games with the Pirates, starting four games. He had three hits and hit one home run in 21 career at-bats. It came in his sixth big-league game, a three-run blast against San Francisco, on April 30, 1989.

"Till the day I leave this earth I think I'll remember that," he said.

On Sept. 25, five members of the Georgia baseball team, led by Stinson, participated in a protest rally in downtown Athens after a Louisville, Ky., grand jury did not file charges against the police officers for the killing of Breonna Taylor in March.

Stinson, who'd organized another protest about a month before, spoke at the rally of about 150 people. He said it was a very powerful experience.

"It's a crazy feeling, it's a feeling like I've never felt before," he said a few days after the rally. "It's one of the best feelings ever, and I told them that when I was speaking. It just gives me a rush seeing everybody come together for a common cause. Seeing us screaming in the streets and marching in the streets, it's just so empowering."

The killings of George Floyd and Taylor, among many others, by police in 2020, which sparked the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement and led to protests throughout the country and around the globe, "really just started a fire deep inside of me," Stinson said.

"My parents have always taught me about social injustice, they've always made sure I knew about Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, people like that, and I've always looked up to them as leaders. I never expected myself to become one, to follow in their footsteps and lead toward change and lead in the right direction."

Carter and his wife, Cindy, have twin 20-year-old sons, Aaron and Josh. When Aaron was asked to speak at a rally in Columbia, Md., it was a very emotional experience for his father.

"It brought me to tears to see your own son just speaking so eloquently and professionally, and from a place of hurt," Carter said. "We don't know how each individual looks at the protest, looks at the police brutality, the racism that has gone on, so I was very proud of him."

During his years at Georgia, Carter experienced a few racist incidents, he said. "I was called the N-word by students on that campus," he said, and he remembers playing a series at Mississippi State, in 1986, when some people in the stands "called me every name in the book."

With teammates like Scott Broadfoot and Steve Muh, Carter said, as well as African American friends on other Georgia teams, he had a support system, a "band of brothers," to help him through the difficult times.

"Those events happened and I overcame those events to actually have a pretty good two-year career at Georgia," Carter said. "Those things, to me, have propelled me into the man that I am today, that's trying to raise two Black young men and tell them about things like that, that happened in the past."

Wrapping up the Zoom meeting, Carter had some words of wisdom for his new friend in Stinson, words that apply to all Georgia student-athletes and everyone else, as well:

"Take advantage of every opportunity that's bestowed to you. In-season reps, out-of-season reps, work when other players are not working," he said. "When I went to Georgia I was probably a good prospect, but when I left Georgia I was a great prospect, so they got me better. ... In the end, it's about you taking care of what you can take care of with the day that you have. We all know that tomorrow's not promised to any of us, so use today as a gift because it is the present."

Staff Writer

Where Steve Carter has been, Josh Stinson would like to go: the big leagues. Where Stinson is now, as an African American on the Georgia baseball team, Carter was more than 30 years ago.

Recently, Carter and Stinson participated in a Zoom meeting, sharing their stories and experiences in baseball, as Bulldogs, and beyond. Stinson, 20, is in his second season with the Bulldogs, still technically a freshman since last season was cut short by the pandemic. Carter, 56, lives in the Washington, D.C., area and is the Deputy Director for Facility Operations for The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, Parks and Recreation.

In 1986, Carter became the first African American scholarship baseball player at Georgia. He was a pioneer and didn't know it, only learning that he was the first earlier this month.

"When I first stepped foot in Athens, it was beautiful, it was a great campus, a great baseball environment, and the first day of practice it did not matter to me that all of my teammates did not look like me," he said. "What mattered to me is we all had the common bond to be better baseball players and better representatives of the community."

Stinson is an outfielder from Lawrenceville, Ga., and playing baseball for Georgia is "like a dream come true," he said.

"Just always seeing Georgia on TV, always hearing about Georgia and how good of a school it is, and having the opportunity to come here, it's just something that I feel like I'm supposed to be here and I'm just thankful that I am here," he said. "It's been a really good transition from high school to here. Everybody's been so accepting and just ready to work and help me out, help me fulfill my potential and become the best baseball player, student and person that I can be."

Growing up "a country boy" in Charlottesville, Va., Carter played multiple sports and saw more diversity in football and basketball than he did baseball, which he said "probably had three or four African American players" on his high school team. Stinson, who attended Grayson High School, a sports powerhouse in the state, had a similar experience in his years playing football and baseball.

"Baseball's not as diverse but it's still pretty open," Stinson said. "Even though there weren't as many African Americans or Black people on my teams, they never really looked at me as any different. They were always pretty open to me, they wanted to be friends with me, like they were my teammates before color even mattered."

Georgia's baseball team had two African American players on the roster last season and there are five in 2021 as the 12th-ranked Bulldogs open their season this weekend with a four-game series against Evansville at Foley Field.

The Bulldogs don't have that "many people that look like me," Stinson said, "but they were still open to taking me in and they still got to know me. I feel like they respect me as a person, so all is good."

During his two seasons with the Bulldogs, in 1986 and '87, after starting college at Hagerstown (Md.) Community College, Carter led the team in at-bats each year. In 1986, he led Georgia in hits (73), runs scored (65) and stolen bases (10). As a senior in 1987, Carter was an All-SEC outfielder on the Bulldogs' first team to make it to the College World Series. In seven postseason games that season, Carter hit .345 and drove in nine runs.

Carter was one of six Bulldogs selected in the 1987 MLB Draft, picked in the 17th round by the Pirates. Back in high school near Charlottesville, Va., Carter's coach was a scout for the Pirates, so it was a relationship many years in the making.

Playing for the Pirates' Triple-A club in Buffalo in 1989, the team was on the road in Nashville, Tenn., when Carter got "the call of a lifetime." Andy Van Slyke, one of the Pirates' star outfielders, was injured and Carter was being called up to the big leagues. He made his Major League debut that night, against the Montreal Expos.

Before leaving Nashville to join the Pirates, he had to call his mom who had raised four boys by herself.

"I said, 'Mom, I'm going to the big leagues.' And then you just heard silence from both us," he said. "We were weeping and crying, and she said, 'What does this mean?' I said, 'Mom, it means I fulfilled a dream.' From a snotty-nosed, buck-toothed, nappy-head boy that had holes in his shoes and people used to laugh at, we were going to the big leagues."

As Carter told the story, it was impossible not to get goosebumps.

"Just knowing that all your hard work paid off, that's got to be a moment like no other, a moment you're going to remember for the rest of your life," Stinson told him. "I just hope that one day I can feel that moment or experience that moment in some way, and to just know that everything I did was worth it."

In more than eight years as a professional baseball player, Carter played in 14 games with the Pirates, starting four games. He had three hits and hit one home run in 21 career at-bats. It came in his sixth big-league game, a three-run blast against San Francisco, on April 30, 1989.

"Till the day I leave this earth I think I'll remember that," he said.

On Sept. 25, five members of the Georgia baseball team, led by Stinson, participated in a protest rally in downtown Athens after a Louisville, Ky., grand jury did not file charges against the police officers for the killing of Breonna Taylor in March.

Stinson, who'd organized another protest about a month before, spoke at the rally of about 150 people. He said it was a very powerful experience.

"It's a crazy feeling, it's a feeling like I've never felt before," he said a few days after the rally. "It's one of the best feelings ever, and I told them that when I was speaking. It just gives me a rush seeing everybody come together for a common cause. Seeing us screaming in the streets and marching in the streets, it's just so empowering."

The killings of George Floyd and Taylor, among many others, by police in 2020, which sparked the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement and led to protests throughout the country and around the globe, "really just started a fire deep inside of me," Stinson said.

"My parents have always taught me about social injustice, they've always made sure I knew about Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, people like that, and I've always looked up to them as leaders. I never expected myself to become one, to follow in their footsteps and lead toward change and lead in the right direction."

Carter and his wife, Cindy, have twin 20-year-old sons, Aaron and Josh. When Aaron was asked to speak at a rally in Columbia, Md., it was a very emotional experience for his father.

"It brought me to tears to see your own son just speaking so eloquently and professionally, and from a place of hurt," Carter said. "We don't know how each individual looks at the protest, looks at the police brutality, the racism that has gone on, so I was very proud of him."

During his years at Georgia, Carter experienced a few racist incidents, he said. "I was called the N-word by students on that campus," he said, and he remembers playing a series at Mississippi State, in 1986, when some people in the stands "called me every name in the book."

With teammates like Scott Broadfoot and Steve Muh, Carter said, as well as African American friends on other Georgia teams, he had a support system, a "band of brothers," to help him through the difficult times.

"Those events happened and I overcame those events to actually have a pretty good two-year career at Georgia," Carter said. "Those things, to me, have propelled me into the man that I am today, that's trying to raise two Black young men and tell them about things like that, that happened in the past."

Wrapping up the Zoom meeting, Carter had some words of wisdom for his new friend in Stinson, words that apply to all Georgia student-athletes and everyone else, as well:

"Take advantage of every opportunity that's bestowed to you. In-season reps, out-of-season reps, work when other players are not working," he said. "When I went to Georgia I was probably a good prospect, but when I left Georgia I was a great prospect, so they got me better. ... In the end, it's about you taking care of what you can take care of with the day that you have. We all know that tomorrow's not promised to any of us, so use today as a gift because it is the present."

Assistant Sports Communications Director John Frierson is the staff writer for the UGA Athletic Association and curator of the ITA Men's Tennis Hall of Fame. You can find his work at: Frierson Files. He's also on Twitter: @FriersonFiles and @ITAHallofFame.

Players Mentioned

OF/INF

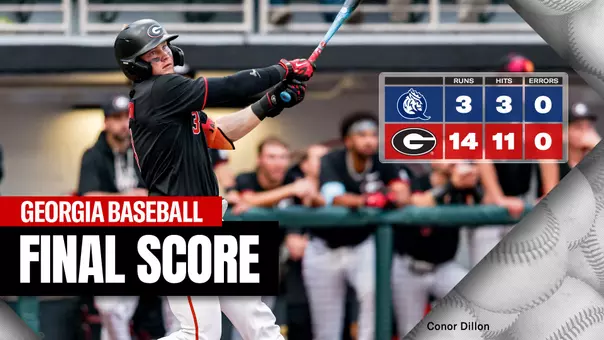

/ BaseballGeorgia Baseball vs Queens Sunday - TV HighlightsGeorgia Baseball vs Queens Sunday - TV Highlights

Sunday, March 08

Georgia Baseball vs.Queens - Postgame InterviewsGeorgia Baseball vs.Queens - Postgame Interviews

Sunday, March 08

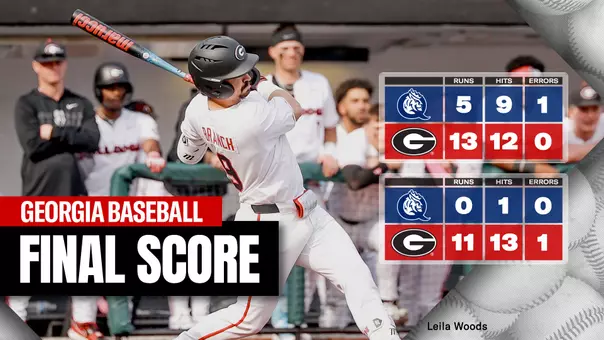

Georgia Baseball vs Queens University - Doubleheader Postgame InterviewsGeorgia Baseball vs Queens University - Doubleheader Postgame Interviews

Saturday, March 07

Georgia Baseball vs Queens Saturday Doubleheader - TV HighlightsGeorgia Baseball vs Queens Saturday Doubleheader - TV Highlights

Saturday, March 07